Monday, December 26, 2005

The Man In Black

On Christmas evening, I had a musical revelation of sorts.

I was in between appointments at City Hall, so I stepped into Gramophone music store, where I’ve scored some sweet deals on blues CDs previously. Of course, that was even before they were called Gramophone, I think it was Music Warehouse or something like that. As a sign of the times though, these days its teenyboppers, new age shtick, bastardized variants of jazz and whatever sells these days that occupies most of the shelf space.

After casting a disdainful eye at the increasingly anorexic blues section, I strolled down the same aisle just idly looking around, not hoping to find much in particular. As chance would have it, I found myself in the country section, these days known more for the buxom blondes and pseudo-outlaw crooners in fancy hats. Somehow country seems to have acquired a bad rep over here in my age group, no thanks to the increasing popularity of line dancing among retirees.

It may have been a long time ago, but my first exposure to music was actually through country. Back when I would ride in my dad’s car, the radio was always tuned to 90.5 FM, which broadcasted a heavy diet of Kenny Rogers and John Denver. To this day, I can still remember a few of Kenny Roger’s choruses, like “Lucille” and “The Gambler”. The images of the stories being told remain fresh in my mind years later, much like the pictures you form in your head when you read an engaging book.

If I ever do get to meet him in person though, I’d want to tell him that his overpriced chicken sucks.

Back to Gramophone. In my state of idle browsing, I somehow stumbled upon a small cluster of Johnny Cash CDs nestled away in a corner, all at nicely lowered prices (Hmm, I wonder why). I’d previously heard of Walk The Line, and as of now I’m eagerly awaiting its opening in Singapore. As a primer of sorts, I decided to pick up one of his albums, having only heard bits and pieces here and there before. Always being partial to live albums, I picked up “Johnny Cash at San Quentin”.

Posted by Picasa

Later that evening (the next morning, rather), I popped it into my CD player for a listen before hitting the sack, intending to browse through a magazine as it played.

I didn’t sleep till the whole CD was through, and the magazine lay on my table untouched.

This album was recorded in 1969 at San Quentin Prison, the 4th time that Cash played there. On this occasion, he had just recovered from a drug addiction, gotten married and found renewed faith in his religion. However, his guitar player of 13 years, Luther Perkins, had passed away a few months earlier. With this mixed bag of emotions slung over his shoulder, you’d expect it to show in the music, and it did. His usually thundering voice was strained and his pitching was hardly on form. The arrangements and the rest of the band weren’t as tight as usual, sometimes even his guitar wasn’t in tune.

But something shone through and rose above the technicalities. Here he was, playing for a whole prison-full of what society would consider as scum, with barely enough armed guards patrolling the aisles. Earlier on, the warden had already advised him “Mr Cash, don’t you dare look these men in the eyes. I’d suggest you and your family (he had his new wife and sisters on stage with him) look just over their heads at the wall in the back of the room.”

He threw that advice to the wind, and gave a performance that might have incited a prison riot. His banter in between songs, his choice of material, his whole stage persona indicated his personal empathy for the inmates and a genuine desire to reach out to them, and they responded in kind with loud cheers, hoots and unbridled applause that no tuxedo-wearing upper-crust types could have mustered at Carnegie Hall.

His impassioned songs told profound stories in simple words, of the life of freedom that the inmates dreamt of, of the anger against injustice. Some songs were just plain silly, bringing much needed humour into the grey stone walls, while the gospel numbers preached the word to those whom few would consider preaching to.

The brash spirit of his performance resonated with the incarcerated souls, emanating more anti-establishment credibility than any punk band can claim, boldly going where no smack-talking, swaggering rock stars would, with his wife and sisters in tow no less.

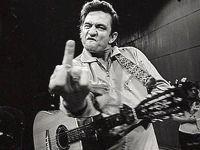

When the cameras kept blocking him from the audience and refused to move, here's what he had to say.

Posted by Picasa

Perhaps the definitive song of this album is San Quentin, a sure hit with the inmates so much so that they demanded a replay right away. You can definitely guess which lines garnered the most cheers.

San Quentin, you've been livin' hell to me

You've hosted me since nineteen sixty three

I've seen 'em come and go and I've seen them die

And long ago I stopped askin' why

San Quentin, I hate every inch of you.

You've cut me and have scarred me thru an' thru.

And I'll walk out a wiser weaker man;

Mister Congressman why can't you understand.

San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think I'll be different when you're through?

You bent my heart and mind and you may my soul,

And your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall and may I live to tell.

May all the world forget you ever stood.

And may all the world regret you did no good.

San Quentin, you've been livin' hell to me.

This whole album got me thinking about what music means to different people. For most, music is something playing in the background, secondary to the task at hand like driving, studying, dancing or whatever. For some of us, music is a way of life in itself, not an accessory to it.

But when you strip a person of everything he has, his freedom, dignity and identity, music still remains a beacon of hope and offers a semblance of normalness to what is otherwise an instituted life. Much like that scene from Shawshank Redemption where Dufrene sneaked into the prison broadcasting station to play a classical record, which Morgan Freeman’s character says “made them feel human again.”

I wouldn’t say I’ve ever lived anything remotely resembling that kind of life, not even National Service, but I can definitely vouch for how music has gotten me out of the low points.

“Johnny Cash at San Quentin” captures such a moment of release and reprieve for the inmates brought about by a charismatic performer who transcends genres, boundaries and social divides, who spoke to the condemned as he would any audience.

I was in between appointments at City Hall, so I stepped into Gramophone music store, where I’ve scored some sweet deals on blues CDs previously. Of course, that was even before they were called Gramophone, I think it was Music Warehouse or something like that. As a sign of the times though, these days its teenyboppers, new age shtick, bastardized variants of jazz and whatever sells these days that occupies most of the shelf space.

After casting a disdainful eye at the increasingly anorexic blues section, I strolled down the same aisle just idly looking around, not hoping to find much in particular. As chance would have it, I found myself in the country section, these days known more for the buxom blondes and pseudo-outlaw crooners in fancy hats. Somehow country seems to have acquired a bad rep over here in my age group, no thanks to the increasing popularity of line dancing among retirees.

It may have been a long time ago, but my first exposure to music was actually through country. Back when I would ride in my dad’s car, the radio was always tuned to 90.5 FM, which broadcasted a heavy diet of Kenny Rogers and John Denver. To this day, I can still remember a few of Kenny Roger’s choruses, like “Lucille” and “The Gambler”. The images of the stories being told remain fresh in my mind years later, much like the pictures you form in your head when you read an engaging book.

If I ever do get to meet him in person though, I’d want to tell him that his overpriced chicken sucks.

Back to Gramophone. In my state of idle browsing, I somehow stumbled upon a small cluster of Johnny Cash CDs nestled away in a corner, all at nicely lowered prices (Hmm, I wonder why). I’d previously heard of Walk The Line, and as of now I’m eagerly awaiting its opening in Singapore. As a primer of sorts, I decided to pick up one of his albums, having only heard bits and pieces here and there before. Always being partial to live albums, I picked up “Johnny Cash at San Quentin”.

Posted by Picasa

Later that evening (the next morning, rather), I popped it into my CD player for a listen before hitting the sack, intending to browse through a magazine as it played.

I didn’t sleep till the whole CD was through, and the magazine lay on my table untouched.

This album was recorded in 1969 at San Quentin Prison, the 4th time that Cash played there. On this occasion, he had just recovered from a drug addiction, gotten married and found renewed faith in his religion. However, his guitar player of 13 years, Luther Perkins, had passed away a few months earlier. With this mixed bag of emotions slung over his shoulder, you’d expect it to show in the music, and it did. His usually thundering voice was strained and his pitching was hardly on form. The arrangements and the rest of the band weren’t as tight as usual, sometimes even his guitar wasn’t in tune.

But something shone through and rose above the technicalities. Here he was, playing for a whole prison-full of what society would consider as scum, with barely enough armed guards patrolling the aisles. Earlier on, the warden had already advised him “Mr Cash, don’t you dare look these men in the eyes. I’d suggest you and your family (he had his new wife and sisters on stage with him) look just over their heads at the wall in the back of the room.”

He threw that advice to the wind, and gave a performance that might have incited a prison riot. His banter in between songs, his choice of material, his whole stage persona indicated his personal empathy for the inmates and a genuine desire to reach out to them, and they responded in kind with loud cheers, hoots and unbridled applause that no tuxedo-wearing upper-crust types could have mustered at Carnegie Hall.

His impassioned songs told profound stories in simple words, of the life of freedom that the inmates dreamt of, of the anger against injustice. Some songs were just plain silly, bringing much needed humour into the grey stone walls, while the gospel numbers preached the word to those whom few would consider preaching to.

The brash spirit of his performance resonated with the incarcerated souls, emanating more anti-establishment credibility than any punk band can claim, boldly going where no smack-talking, swaggering rock stars would, with his wife and sisters in tow no less.

When the cameras kept blocking him from the audience and refused to move, here's what he had to say.

Posted by Picasa

Perhaps the definitive song of this album is San Quentin, a sure hit with the inmates so much so that they demanded a replay right away. You can definitely guess which lines garnered the most cheers.

San Quentin, you've been livin' hell to me

You've hosted me since nineteen sixty three

I've seen 'em come and go and I've seen them die

And long ago I stopped askin' why

San Quentin, I hate every inch of you.

You've cut me and have scarred me thru an' thru.

And I'll walk out a wiser weaker man;

Mister Congressman why can't you understand.

San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think I'll be different when you're through?

You bent my heart and mind and you may my soul,

And your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall and may I live to tell.

May all the world forget you ever stood.

And may all the world regret you did no good.

San Quentin, you've been livin' hell to me.

This whole album got me thinking about what music means to different people. For most, music is something playing in the background, secondary to the task at hand like driving, studying, dancing or whatever. For some of us, music is a way of life in itself, not an accessory to it.

But when you strip a person of everything he has, his freedom, dignity and identity, music still remains a beacon of hope and offers a semblance of normalness to what is otherwise an instituted life. Much like that scene from Shawshank Redemption where Dufrene sneaked into the prison broadcasting station to play a classical record, which Morgan Freeman’s character says “made them feel human again.”

I wouldn’t say I’ve ever lived anything remotely resembling that kind of life, not even National Service, but I can definitely vouch for how music has gotten me out of the low points.

“Johnny Cash at San Quentin” captures such a moment of release and reprieve for the inmates brought about by a charismatic performer who transcends genres, boundaries and social divides, who spoke to the condemned as he would any audience.